In my last few posts I’ve pondered the issue of how insecure WordPress installations have become. Here’s an interesting thing to try if you run a WordPress site; install the 404 to 301 plugin and in its settings check the “Email notifications†option and enter an email address in the “Email address†field. Now, whenever a nonexistent URL is requested, you’ll get notified and, at least for me, it’s been pretty interesting to see how hackers attempt to enter my WordPress installations.Â

I installed this plugin on one of my projects, vaporregistry.org (it’s due for a major architectural refresh in the next few weeks), and I’ve been collecting these 404s, the majority of which are obvious hack attempts because they’re requests for resources that don’t exist on my site.

Now, this site is in startup mode; it’s a specialized product registry and doesn’t get a huge amount of traffic yet, but in addition to the thousands of normal requests there were 2,250 failed requests in the 90 days between January 22 and April 18. Each of these events were recorded in an email with a date and time stamp, an IP address, and the requested resource.Â

I’d set up a Gmail filter to label these messages so I used Google’s Takeout service to download them in mbox format. Mbox is a simple text only format so I opened the file in MS Excel and sorted the entire file alphabetically. I then found the block of content I wanted, which looked like this:

pBummer! You have one more 404/ptabletrthIP Address/thtd202.75.55.176/td/trtrth404 Path/thtd/manage/fckedit/editor/fckeditor.original.html/td/trtrthUser Agent/thtdMozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; Trident/4.0)/td/tr/table

… and then I deleted all but those lines. For the purposes of this analysis I didn’t need the date and time from the Date: fields but getting those lines associated with the message text would have been easy (email me if you want to know how to do it). I then deleted everything before the IP address, replaced the HTML between the IP address and the text of the 404 path with a comma followed by a space and a double quote, and replaced the next block of HTML up to the actual user agent string with double quote, comma, space, double quote, and then removed the trailing HTML with a double quote to wind up with:

202.75.55.176, “/manage/fckedit/editor/fckeditor.original.htmlâ€, “Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; Trident/4.0)â€

I now had a comma separated variable file with 2,500 records. A word to the wise here: Watch out that the editor you’re using doesn’t use Smart Quotes because a lot of what comes later in mangling this data will fail in bizarre ways if you’re not using regular double quotes and wasted hours of your life as I have done many times. You have been warned.

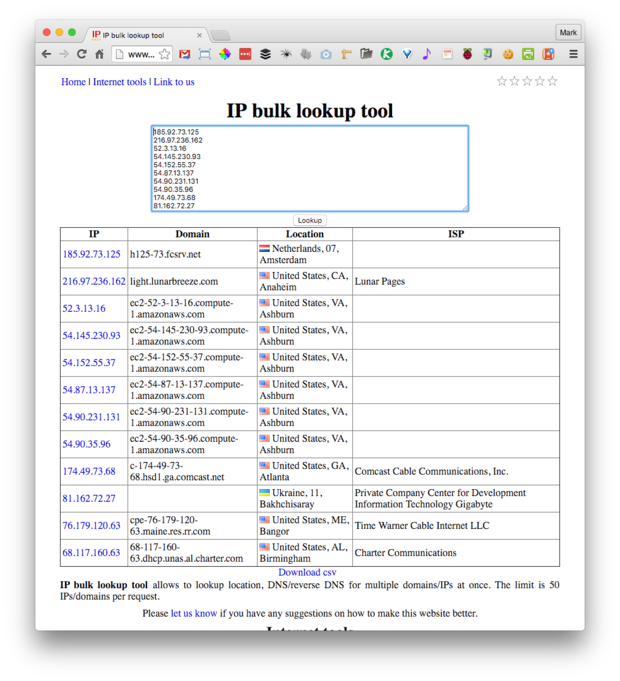

I opened the CSV file in Excel and now I needed to find out where the IP addresses originated. Because each IP address could generate one or more events I selected all of them and created a pivot table (I love Excel!) to extract a list of unique IP addresses. This gave me a list of 198 addresses which for the sake of speed I decoded using InfoByIP.com’s bulk lookup tool (I could have written a Python program to do all this but short on time, yadda, yadda, yadda …).

InfoByIP.com IP bulk lookup tool

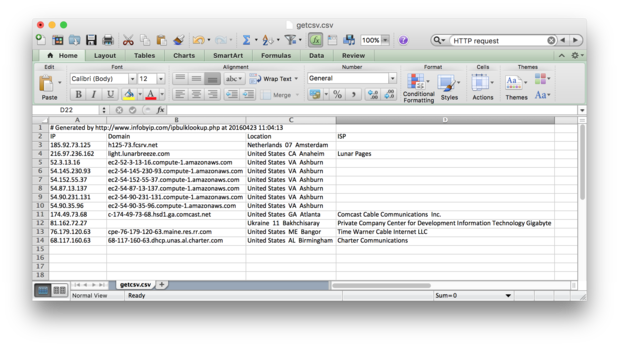

This service only accepts 50 IP addresses at a time so I pasted multiple blocks into the data field and downloaded each of the CSV results files and merged them into a single spreadsheet.

InfoByIP.com An example of the CSV encoded data output by the IP bulk lookup tool

Now I had to deal with the agent strings and for that I used UseragentAPI which is a database of user agent strings that can be accessed via a REST API.

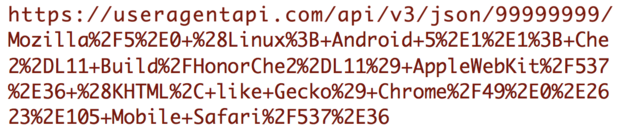

UseragentAPIÂ for decoding user agent strings

You can sign up for a free account (this allows for 1,000 requests per day) and you can use the wget command line utility to run your queries in bulk (I used wget rather than cURL for its bulk processing ability). I used Excel to format the requests, taking the agent strings and embedding them into the URLs to be executed. Here’s an agent string:

Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; Android 5.1.1; Che2-L11 Build/HonorChe2-L11) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/49.0.2623.105 Mobile Safari/537.36

This has to be URL encoded which I did with an Excel formula using a VB script function called URLEncode (the “99999999â€Â  is where the access key that you get when you sign up goes):

=“https://useragentapi.com/api/v3/json/99999999/"URLEncode(D12)

The URLEncode function is from a post on the Sevenwires blog :

Function URLEncode(ByVal Text As String) As StringDim i As IntegerDim i As IntegerDim acode As IntegerDim char As StringURLEncode = TextFor i = Len(URLEncode) To 1 Step -1acode = Asc(Mid$(URLEncode, i, 1))Select Case acodeCase 48 To 57, 65 To 90, 97 To 122' don't touch alphanumeric charsCase 32' replace space with "+"Mid$(URLEncode, i, 1) = "+"Case Else' replace punctuation chars with "%hex"URLEncode = Left$(URLEncode, i-1) "%" Hex$(acode) Mid$(URLEncode, i+1)End SelectNextEnd Function

And here it is that agent string embedded in a request URL:

I then saved the request URLs in a plain text file called urls.txt. Be warned: Blank agent strings will return nothing and mess up the next step. Also make sure that you have the correct line endings in the text file for the operating system you’re on; get that wrong and you’ll probably end up sending all the entries as a single huge string that will cause UseragentAPI to barf.

Next, I went to the command line and used the wget utility:

wget -i urls.txt -O agents.json

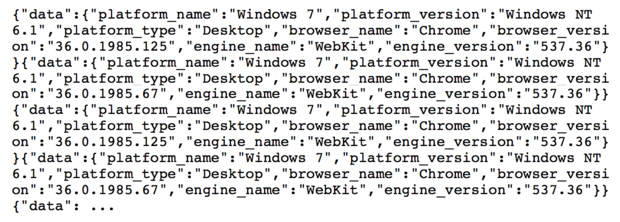

The -i argument specifies that the input will come from urls.txt and the -O specifies that the output should be appended to agents.json. The output file is, as you might guess, a JSON format file and you’ll find that all the results are munged together so you have what amounts to a single string in the file like this:

Â

So I hauled the content into Word and did a Replace All of the string }}{ (that’s the end of each result followed by the start of the next with }}^p{ (the ^p is Word’s meta-character for a newline) to get one entry per line:

Next, using Convert JSON to CSV I wound up with another CSV file of the disassembled user agent string that I opened in Excel, copied, then pasted into my analysis spreadsheet. I inserted the new data which was in the same order as the original user agent strings and because I checked the input request to make sure none were blank, the input and output data aligned exactly in the spreadsheet.

Convert JSON to CSV is terrific: Give it multiple strings of JSON and it will figure out how to unpack them into a single CSV file adding columns as it finds them defined in each line of JSON. Very slick.Â

Finally I had to slice and dice the event requests which was just some simple Excel work to identify which entries had specific types of requests such as using PHP or trying to access admin features.

From the original 2,500 events I was able to exclude 424 events which came from various search engine bots looking for resources (I’m pretty sure these never existed on the site but that they apparently don’t want give up on them), as well as a bunch of my own test requests, and some other requests that were innocent.

There were also 150 events generated by SiteLock. When I set up the SSL certificate for the site via my ISP, Bluehost, the service also included a free basic malware scan by SiteLock. It turns out that Sitelock has been requesting the same nonexistent resource for a long time and never telling me there’s a problem or asking me about it. Finding out what’s going on with Sitelock is most likely a rat hole I need to avoid for the sake of getting work done.

So, the remaining 1,822 events are suspicious and there are some interesting things to learn from them. One of these is that many hackers are apparently pretty dim. Just over 10% of the events (192) came from 90 IP unique addresses and sent the same request two or more times. This is like phoning someone and being told it’s the wrong number and then phoning again to make sure. Du’oh.

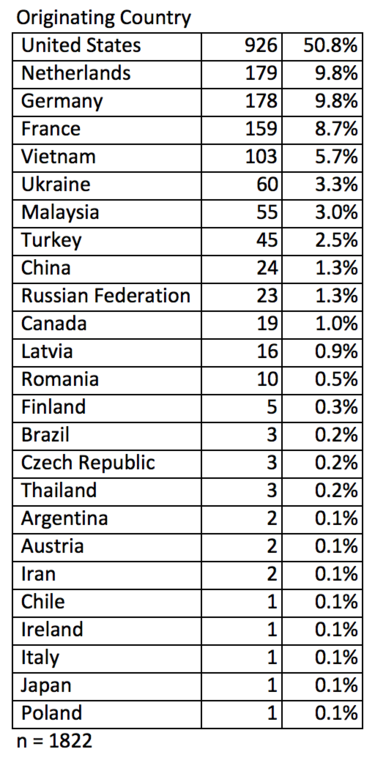

The next question is where do these hacking attempts come from? For my site, just over half come from the U.S. while Russia and China have surprisingly low numbers. I suspect that more popular sites would see quite different geographic distributions.

What are hackers using as attack platforms? In over 64% of events we don’t know as there’s no user agent string and if you were building an automated hacking defense system the attribute of lacking of a user agent string or one that isn’t recognized would be highly indicative.

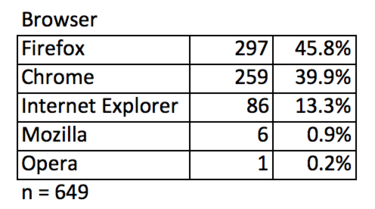

Of those with recognizable UA strings, Windows in all versions makes up almost 26% of all attacks. Linux (8.8%) is also common, beaten only by Windows Vista (13.9%). It’s probable that events without a UA string are the result of programs accessing your content rather than web browsers making requests. Where there is a UA string, almost 46%% indicated the browser was Firefox and Chrome, at almost 40%, was a strong second. Internet Explorer was a weak third at just over 13%.

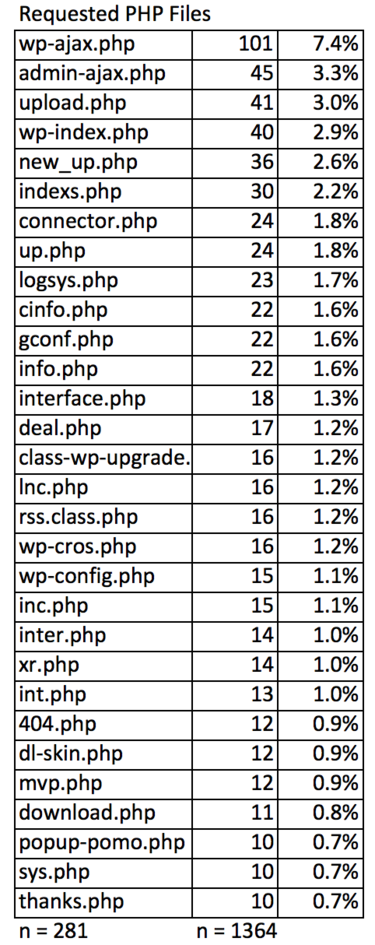

While the foregoing stats are sort of interesting, the real meat is in what hackers are trying to do in their requests: Just over 73% of all events requested a PHP file; 37% were looking for an executable under the /wp-content subdirectory or its subdirectories; 10.8% and 9.3% were trying to invoke something in an editor or author labelled context respectively; and 5.9% were hoping to find something executable with the name “managerâ€.

I extracted a list of the unique 281 PHP files that 73% of events requested (you can download the data set here). I also broke out the 23 requests where two PHP files were named, the first one being asked to do something such as download the second (you can download the data set here).

My conclusion from all of this slicing and dicing is that hackers have figured out lists of vulnerabilities which involve invoking PHP applications. These vulnerabilities have become well-known enough to be in general use and trying these out on your own site may reveal issues, particularly if you’re behind in your updates (you can download the list of Requested URL Tails here).Â

Want the spreadsheet containing all of the individual events? Drop me a note at feedback@gibbs.com.

Comments? Thoughts? Suggestions? Lay some feedback on me via email or comment below then follow me on Twitter and Facebook.

Article source: http://www.networkworld.com/article/3060774/security/analyzing-real-wordpress-hacking-attempts.html