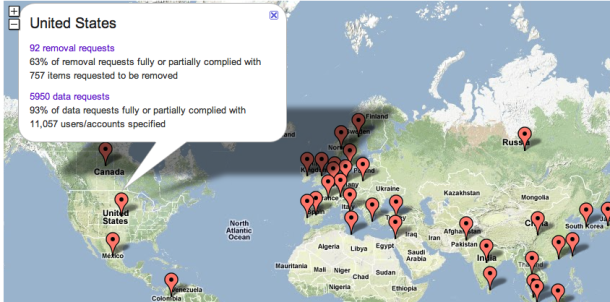

This interactive map from Google’s latest Transparency Report shows the amount of user account data governments around the world request.

(Credit:

Google)

A new report from Google shows a rise in government requests for user account data and content removal, including a request by one unnamed law enforcement agency to remove YouTube videos of police brutality–which the company refused.

The latest Google Transparency Report, released today, also shows historic traffic patterns on Google services via graphs with spikes and drops indicating outages that, in some cases, indicate attempts by governments to block access to Google or the Internet. For instance, all Google servers were inaccessible in Libya during the first six months of this year, as was YouTube in China.

But the truly interesting data are the statistics on requests made to the company by governments for either access to user data or to remove content.

Some countries had large amounts of user data requests. The United States leads that pack, with 5,950 such requests pertaining to more than 11,000 users or accounts, and to which Google complied 93 percent of the time. That’s up from about 4,600 requests in the second half of last year. Other countries seeking lots of user data were India (more than 1,700 requests involving more than 2,400 accounts), France, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Google says it complied most of the time in those cases, except in France.

The actual numbers are likely larger than what is reported because Google is prohibited by law from revealing information on requests from intelligence agencies such as the National Security Agency or FBI, notes online privacy advocate Chris Soghoian, who released a report on law enforcement surveillance earlier this year.

“Google doesn’t say how many of the thousands of requests they get a year are compelled (via a formal legal process) and how many are emergency requests,” which they aren’t obligated to comply with, he said. “This is where Google could truly demonstrate its commitment to privacy…We know that Verizon gets 90,000 requests a year, and 25,000 are emergency requests for which there is no court order. It’s likely Google is getting a similar percentage.”

But Soghoian commended Google on providing the figures on the numbers of accounts that officials are seeking information from in addition to the number of requests. “This is a useful data point because one request could be for 50 accounts,” he said. “It’s great that Google is providing this.”

Also of note in the report were the attempts by governments to get Google to remove content, from YouTube videos to blogs to ads. Google said it received 29 percent more requests for user data from government sources during the first half of this year than during the previous six months, and 70 percent more requests to remove content in that period. The report called out the request to remove YouTube videos of police brutality and separate requests from an unnamed different law enforcement agency to remove allegedly defamatory videos, but it said those requests were denied.

In the United States, Google said it received 92 requests to cumulatively remove 757 items, and complied fully or partially in 63 percent of the cases. That compared to 54 requests in the second half of last year. There were 24 court orders related to Web searches, and 26 police or executive requests related to YouTube.

Thailand asked Google to remove 225 videos for allegedly insulting the monarchy, and in response, Google restricted Thai users from accessing 90 percent of the videos. Google also restricted Turkish users’ access to some videos but denied a majority of requests from India to remove videos of protests or videos using offensive language in reference to religious leaders. And when asked by China to remove more than 120 items from Google services, the company declined in nearly all of the cases.

Meanwhile, content removal requests from U.K. officials rose by more than 70 percent. User data requests were up 28 percent in Spain, 38 percent in Germany, 27 percent in France, and 36 percent in South Korea.

Google is hoping to lead by example, and Soghoian called out other companies for not releasing this information too.

“There is simply no excuse for Microsoft, Yahoo, Twitter, and Facebook not to provide the same data,” he said. “These firms monetize our data, and they don’t want to give us any reason or cause for concern about entrusting them with our data, but they all need to step up and follow Google’s lead.”

Asked why Google releases the data, spokeswoman Christine Chen told CNET: “We actually believe being transparent about these numbers can contribute to public discussion about how policies affect access to information on the Internet…We really believe in transparency and free flow of information.”

In a blog post on the report, Dorothy Chou, senior policy analyst at Google, suggested that the ultimate goal with the report is to encourage more user-friendly policies.

“We believe that providing this level of detail highlights the need to modernize laws like the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which regulates government access to user information and was written 25 years ago–long before the average person had ever heard of e-mail,” she wrote. “Yet at the end of the day, the information that we’re disclosing offers only a limited snapshot. We hope others join us in the effort to provide more transparency, so we’ll be better able to see the bigger picture of how regulatory environments affect the entire Web.”

The company participates in the OpenNet Transparency Project, an effort to provide an easy way for companies to share data on government information requests. That project is part of the OpenNet Initiative, whose goal is to “investigate, expose, and analyze Internet filtering and surveillance practices.”

Google began releasing information about government requests for user data and content removal in early 2010, and it aims to release such data every six months.

Article source: http://news.cnet.com/8301-1009_3-20125483-83/google-governments-seek-more-about-you-than-ever/